| Samson Occom's A Sermon Preached at the Execution of Moses Paul, an Indian (1772) and A Choice Collection of Hymns and Spiritual Songs: Intended for the Edification of Sincere Christians, of All Denominations (1774) are believed to be the first two books published in English by a Native American. Considered the first widely read Native American book, Occom's account of his own life was written in 1768. It is also the earliest autobiography written by a Native American. Occom began teaching native students how to speak English using verses on chips of cedar chips. Julia Clark's publication in 1993 of Occom's diaries makes available a forty-six-year record of observations about "Indian ways of everyday life, housing, travel, communication, legal status, politics, and dress." Occom, a Mohegan, was born in 1723 in a wigwam on the west side of the Thames River between New London and Norwich, Connecticut, to Joshua and Sarah Ockham. By midcentury the Mohegans were impoverished by colonial encroachment, having been denied access to fishing sites and hunting grounds that had extended in the time of Uncas -- from whom Occom was said to claim matrilineal descent -- to the Rhode Island and Massachusetts borders. The evangelistic preachers seemed to offer a mode of survival, and at seventeen Occom responded to James Davenport's call to the "Great Awakening" and was converted. On 6 December 1743 he was admitted to a school kept in Lebanon in the home of Eleazar Wheelock, Davenport's Yale classmate and brother-in-law. During his four years there Occom learned to read and write English and studied Greek, Latin, and Hebrew, but he was prevented by poor health and severe eyestrain from going on to college. On 5 November 1766 Wheelock wrote of his gifted student: "Mr. Occum had been long confined by Sore Sickness before he came to me, and was then, and all the time he was with me, [in] a low State of health." Occom taught in New London in the fall of 1747; in 1749 he sought a position as schoolmaster. A group of about thirty-two families of Montauk living at the tip of Long Island invited him to instruct them; unable to offer a salary, they promised to take turns feeding him. Occom wrote to the Boston Board of Correspondents for Propagating Christian Knowledge for permission, thinking that the board would provide financial support for him; but it was not until 1751, after his marriage to one of his students, Mary Fowler, that he was paid the inadequate sum of fifteen pounds a year. The retirement of the local minister, Azariah Horton, in 1757 meant that Occom had to add pastoral duties to his teaching responsibilities, but he was not paid for the extra work. As his family grew, his debts accumulated, so he resorted to farming, fishing, hunting, selling objects he made of cedar (such as churns, buckets, mortars and pestles, and ladles), and rebinding the books in the library of Samuel Buell of Easthampton. On 12 November 1756 Occom was ordained by the New Light Calvinist sect of Connecticut. He passed the rigorous examination for ordination by the Presbytery of Suffolk, Long Island, on 13 July 1757 and was ordained on 29 August 1759. He was to be sent to minister to the Cherokee under the auspices of the Scotch Society of Missions at the substantial salary of seventy pounds a year. Occom was prevented from carrying out the proposed venture by fighting between the Cherokee and settlers who were trying to take over their land; instead, he was sent west to recruit Oneida students for Wheelock's school. With his brother-in-law, David Fowler, he left Connecticut on 10 June 1760 to teach the Oneida in what is now New York and to bring back promising youths. The Oneida chiefs gave Occom and Fowler a wampum belt to bind their friendship when they departed on 19 September 1760. That winter Occom taught himself to speak Oneida so that he would not need an interpreter when he returned in 1762. His third mission was aborted by the Pontiac war of 1763. On 3 April 1764 Occom moved his family to the village of his birth, which by then was called Mohegan; they lost their household goods in a storm during their crossing of Long Island Sound. On the ancestral land where his mother, his sister Lucy, and his brother Jonathan still lived he constructed a two-story house that later became a historic landmark. By this time he and his wife had had seven children: Mary, born in 1752; Aaron, born in 1753; Tabitha, born in 1754; Olive, born in 1755; Christiana, born in 1757; Talitha, born in 1761; and Benoni, born in 1763. In the spring of 1765, after Occom had accompanied him on his sixth tour of the colonies, George Whitefield, the greatest preacher and missionary of his age, considered taking Occom back to England with him; later he suggested that Wheelock bring Occom. On 23 December 1765 Occom and another clergyman, Nathaniel Whitaker, set sail from Boston to raise funds for Wheelock's Indian Charity School; they arrived in England on 3 February 1766. Occom's charismatic preaching elicited donations far in excess of those given to any other colonial institution: he raised £9,497 from 2,169 people in 305 churches in England; and in Scotland, where he displayed the Oneida wampum belt, he raised an additional £2,529. Occom's charm transcended sectarian rivalries, making him a truly ecumenical figure; his tact and diplomacy earned him esteem wherever he spoke. London's leading Baptist, Andrew Gifford, became a friend, and William Warburton, bishop of Gloucester, made "overtures of Episcopal ordination" to him. He was the guest of John Newton, the composer of the hymn "Amazing Grace," at Olney. In Edinburgh Occom modestly declined an honorary doctorate. Occom returned to Mohegan in the fall of 1768 and soon became bitter about his treatment at the hands of whites. He found his wife and children living in poverty, even though Wheelock had promised that they would be cared for while he was in Britain. Also, because Occom had spoken out in favor of a lawsuit to regain Mohegan land that had been fraudulently taken by white colonists (the suit had been decided in the colonists' favor in 1766), a rumor campaign had been started against him. It was to correct these misrepresentations -- that he was not really a Mohegan, that he had not been converted until just before his trip to Britain, and that he was an alcoholic -- that he wrote his ten-page autobiography of 17 September 1768. Furthermore, Wheelock's school, for which Occom had raised so much money, was moved in 1769, over Occom's objections, to Hanover, New Hampshire; as Occom had feared, it ceased to be an Indian school and later became Dartmouth College. Finally, Occom was left without income after a rupture with the Boston board. In his biography, Samson Occom (1935), Harold Blodgett says that rumors that "he had fallen into intemperance" were started because Occom was dizzy from "having been all day without food." According to Leon Burr Richardson, who edited Occom's letters (1933), Occom was so poor that he "drank only cold water." On 2 September 1772 Occom preached a temperance sermon at the execution of Moses Paul, a Christianized Indian who had committed murder while intoxicated and had been sentenced to hang. The sermon attracted a massive audience of people who had heard of the charismatic preacher. It was published the same year. In 1773 Occom and his former pupil Joseph Johnson, who had married Occom's daughter Tabitha, began to plan a migration of the converted New England Indians to land in New York offered to them by the Oneida. Occom's final child, Andrew Gifford, was born in 1774. That same year his collection of hymns, an interdenominational compilation Occom had put together during and after his trip to England, was published. Johnson left for New York first -- the project had really been his idea -- but was killed in the Revolutionary War in 1776. Occom left his family in Connecticut and traveled back and forth to the new settlement in Brothertown, New York, acting as an itinerant preacher along the way. In 1784 he toured New England to raise funds for the settlement, and he collected donations for it for six years. He moved his family to Brothertown in 1789. The migration was impeded by war, by lack of funds, and by extensive litigation over the land, which the Oneida ceded to New York. Occom had befriended legislators in Albany on his many fund-raising trips, and they finally deeded the land to him -- one of the few instances of whites living up to an agreement with Indians. About 250 Indians migrated to Brothertown in 1791. Occom established the first Indian Presbyterian church in Brothertown in 1792; shortly thereafter, on 14 July, he died suddenly while gathering cedar wood with which to complete a churn. Much of the scholarship on Occom has focused on the execution sermon, but the diary he kept from 1743 to 1790 deserves at least equal attention. Among the educational innovations he describes are sets of cards containing Bible verses that he would deal out to children; he would then comment on how each card was appropriate to the child who had drawn it. He also describes how, carrying a copy of his own hymnal in his pocket on his travels, he would lead the singing in the frontier cabins he visited. From his patrons he requested only songbooks. In the introduction to her edition of the diary, Clark says that the work shows the process of Occom's acquisition of English: the early entries are "short, clumsy, inexpressive," while later ones show an expanded vocabulary and improved phrasing. Abbreviated though the entries are, they offer many insights into the narrative gift that made Occom's sermons so memorable; he was noted for his compelling stories. Blodgett quotes one anecdote that remained vivid even after the lapse of seventy-seven years: "An old Indian, he said, had a knife which he kept till he wore the blade out; and then his son took it and put a new blade to the handle, and kept it till he had worn the handle out"; but it remained the same knife. The story serves as an analogy for the resiliency of Indian culture. Occom could wring every possible nuance out of a repeated phrase, as is evident in a letter to Robert Cleveland that is quoted by Blodgett: "You turned yourself out of our School, and You turn'd yourself out of the Church, and you are turning yourself out of the Favour of every Body . . . take Care that you don't turn your Self out of Heaven." Though Blodgett asserts that "there is not a hint of lightheartedness in all his writings, Occom's first biographer, William DeLoss Love, claims that "there was a dry humor in his sayings, at which he never laughed himself, but which must have amused his listeners." Today various groups of indigenous people are basing claims for federal recognition of tribal status on Occom's writings. Among the communities that have cited him in court are the Mohegans of southeastern Connecticut; the Narraganset of Charlestown, Rhode Island; the Pequots of Stonington and Groton, Connecticut; the Niatic of Lyme, Connecticut; the Tunxis, Quinnipiacs, and Wangunks of Farmington, Connecticut; and the Montauks of Long Island, New York. The Mohegan Tribal Council, under the leadership of Courtland Fowler, a descendent of Occom, petitioned for federal recognition in 1984 on the basis of the "Sociocultural Authority" of Occom. Citing the fifty-two roots with healing properties Occom learned of from Ocus, a tribal herbalist and medicine man, in 1761, the Montauk invoke Occom as one who inspired them to preserve their cultural heritage, including their "green medicine," or ethnobotanical knowledge. Thus, more than two hundred years after his death, Samson Occom continues to help his people. References American poetry : the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. 2007. Love, W. D. Samson Occom and the Christian Indians of New England. 1899. Roemer, K. M. Native American writers of the United States. 1997. Occom's Writings Occom, S. A Sermon Preached at the Execution of Moses Paul, an Indian. 1772. Occom, S. A Choice Collection of Hymns and Spiritual Songs: Intended for the Edification of Sincere Christians, of All Denominations. 1774. Occom, Samson. A Short Narrative of my life. 1768. |

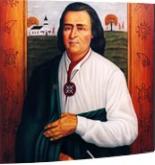

| Samson Occom Mohegan |

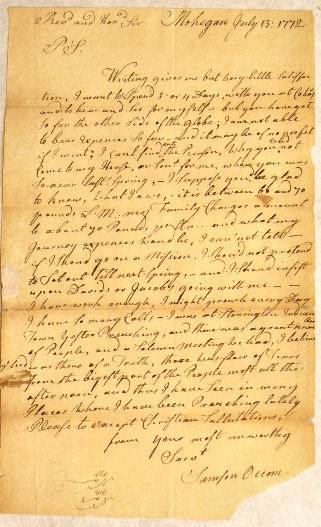

| Letter Writter by Samson Occom in 1772 |

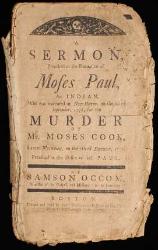

| Samson Occom's A Sermon Preached at the Execution of Moses Paul, an Indian (1772) |